By: Daniel Park (Under supervision of Sarah Bang)

In the final stages of one’s life, it becomes evident that despite everyone’s best efforts, you are approaching the end of your life. During times like this, the focus is shifted to making you as comfortable as possible before their passing. End-of-life care describes the support and medical care given during the time of one’s death. There is no specific point in time when end-of-life care begins or ends; circumstances surrounding the individual and their cause of death vary vastly from person to person. The end of life may also differ depending on the patient’s needs and preferences. Patients may choose to seek treatment in a hospital or facilities, or stay at home until the very end. Often the patient will experience a range of distressing and conflicting emotions, such as anxiety and an intense fear of death, guilt as the patient may feel that they have somehow failed the caregiver and their loved ones, relief that the struggle is finally coming to an end, or anger at their circumstances. According to the National Institute on Aging, during times like this it is important to give the patient care in four areas: physical comfort, fulfilling mental and emotional needs, spiritual needs — resolving regrets, finding meaning in one’s life, or making peace with circumstances —, providing support for practical tasks. By measuring these different factors, one can determine the quality of one’s end-of-life care.

While doing my basic research, I noticed that dying in a patient’s desired place is an important consideration for patients, families, and caretakers and is considered another key measure of the quality of one’s end-of-life care. Historically, dying at home has been an indicator of high-quality end of life care. Palliative care professionals have tried to ensure that dying patients are taken care of by loved ones at home until their final moments. Dying in a familiar environment, such as home, while being surrounded by loved ones helps ease the patient’s mind and give him a comfortable environment to die in. However, there are also preferable alternatives, such as hospitals, senior facilities, and hospices. In a 2016 analysis by Arcadia Healthcare Solutions, they found that spending on those who die in hospitals is seven times more expensive than that on those who die at home. There were likely more tests, procedures, and treatments run on patients in an effort to extend their lives. However, Dr. Richard Parker, a chief medical officer at Arcadia, stated that “[this] intensity of services in hospitals shows a lot of suffering that is not probably in the end going to offer people more quality of life and may not offer them more quantity of life either.” (Kodjak). In the end, all the patients in hospital care died and likely suffered more in hospitals from running tests and getting treatment, rather than spending time more with their loved ones at home in their final moments. Using 2018-2021 Korean-American causes of death data gathered from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention I want to investigate whether Korean Americans, who are older than 55, are getting quality palliative care using place of death in relation to cause of death as an indicator for the quality of end of life care. I will look into the largest cause of death – cardiovascular disease – to compare the different places of its deaths.

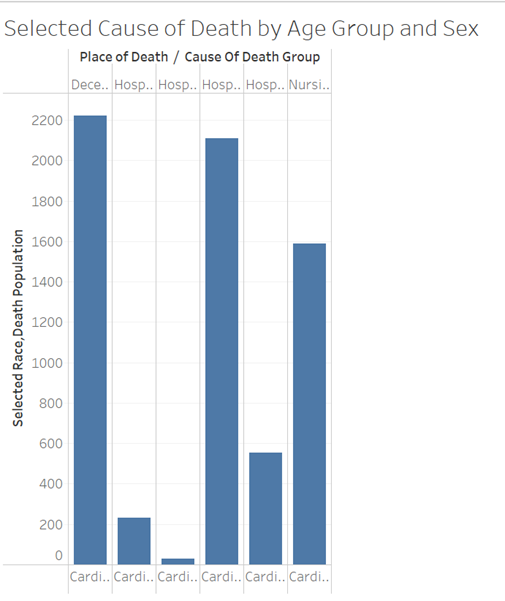

I immediately noticed that the highest place of death was at the decedent’s home (33%). According to WHO, more than four out of five deaths related to cardiovascular disease are due to heart attacks and strokes. Looking at this data, it can be assumed that many of these deaths were from heart attacks and strokes that require immediate medical attention; these Koreans were unable to receive the necessary medical service, leading to their deaths. For further proof, the two lowest places of death were both at the hospital, where patients were either dead on arrival (0.43%) or patients who were outpatients/admitted to ER (8.24%). This shows that people are more likely to survive cardiovascular diseases/heart attacks if hospitalized and immediate action is taken. In areas where many Korean-Americans are living, ambulances may not be readily available or hospitals where people can be treated are not close enough to reach in time for treatment. On the other hand, the fact that so many Korean-Americans die in their homes may also be a sign of high-quality end of life care, as the deceased is in a comfortable and familiar environment, where they are able to spend more time with their loved ones before they pass. The higher death rate in inpatients at hospitals (31.30%) and then hospices (23.60%) shows a lack of quality in end of life care for cardiovascular disease for many Korean-Americans. The National Institute on Aging states that palliative care is medical care for people with terminal illnesses, with the goal of treating their ailment, while hospice care focuses more on the comfort and quality of life of a person who is dying of a serious illness. Korean-Americans who died as inpatients may spend the rest of their days in a stressful hospital environment surrounded by doctors and subjected to different treatments, rather than in the warm environments of a home or hospice, where they would be surrounded by loved ones and friends who could relate to their situation. This may also reveal the deep attachment to family in Korean culture, as Korean-American would be less willing to send family members off into senior facilities. Instead, they would choose to spend their last moments together with their families or seek medical treatment in hopes of saving their family member’s lives.

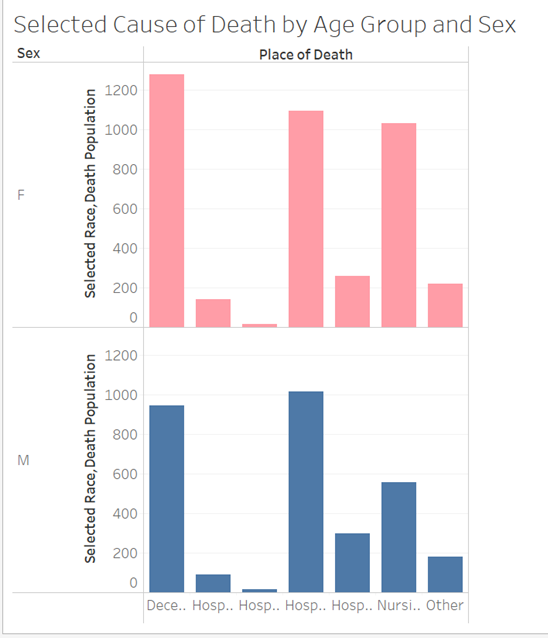

In general, Korean females died 13.28% more than Korean males. This was contrary to my expectations, as I expected men to be more likely to develop heart disease. According to John Hopkins Medicine, while women share many traditional heart disease risk factors, they also have their own unique risk factors as well, such as stress, depression, autoimmune diseases – which are more common in women than men –, and low risk awareness factor. Traditionally, Korean women have taken up the role of the mother and housewife in society, especially in older generations. In the 1960s, an average Korean woman had about six children. The stress of raising so many children and a weakened immune system from giving birth to so many children may be a factor in why Korean females from ages 55+ were more likely to die of heart disease. However, Korean females also had higher rates of dying at home and in hospices than Korean males, indicating that Korean females had a higher-quality of end of life care than Korean males. Korean males also had a higher rate of inpatient deaths in hospitals than at home, meaning that Korean men are more less likely to receive high quality end of life care for cardiovascular diseases than they are to receive lower quality care.

My findings show that most Koreans who are at least fifty-five and have heart disease are able to find high quality end of life care. However, there also remains a lack of immediate medical service attention for Koreans who suffer a heart attack or stroke and hospice care goes severely underutilized by the Korean population. By making these issues known, I intend to inform readers about end of life care and how Korean culture may affect the way Korean Americans seek end of life care and the quality of the end of life care they receive. Seeking treatment for heart disease or staying at home with family is reasonable and perfectly understandable, but I hope that Korean Americans will become more open to the idea of hospice care as an alternative for end of life care. I hope that more Korean Americans will become educated and seek higher quality end of life care towards the end of their life and that more Korean Americans will become educated and seek higher quality end of life care towards the end of their life.

“End of Life End-of-Life Care.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 7 Sept. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/end-of-life/basics/endoflife-care/hlv-20049403.

Robinson, Lawrence, et al. “Late Stage and End-of-Life Care.” HelpGuide.Org, 16 June 2023, www.helpguide.org/articles/end-of-life/late-stage-and-end-of-life-care.htm.

“What Are Palliative Care and Hospice Care?” National Institute on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.nia.nih.gov/health/hospice-and-palliative-care/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care. Accessed 16 Jan. 2024.

Rummans, Teresa A., et al. “Maintaining Quality of Life at the End of Life – Mayo Clinic Proceedings.” Maintaining Quality of Life at the End of Life, Dec. 2000, www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(11)63032-2/fulltext.

García-Sanjuán, Sofía, et al. “Levels and Determinants of Place-of-Death Congruence in Palliative Patients: A Systematic Review.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 16 Dec. 2021, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.807869/full#B4.

“Providing Care and Comfort at the End of Life.” National Institute on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.nia.nih.gov/health/end-life/providing-care-and-comfort-end-life#practical. Accessed 16 Jan. 2024.

O’Neill, Aaron. “South Korea: Fertility Rate 1900-2020.” Statista, 21 June 2022, www.statista.com/statistics/1069672/total-fertility-rate-south-korea-historical/.

Staff, Arcadia. “The Final Year: Visualizing End of Life.” Arcadia, 26 Apr. 2016, arcadia.io/resources/final-year-visualizing-end-life.

Barouch, Lili. “Heart Disease: Differences in Men and Women.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, 5 Jan. 2023, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/heart-disease-differences-in-men-and-women.

![[2024 KD Data Journalist Internship: Project Results ②] “Whose Footsteps will Asian Americans follow? A Close Look at Race as a Factor in Natality”](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/image-82-218x150.png)

![[2024 KD Data Journalist Internship: Project Results ①] “Analyzing Theft Trends in Los Angeles: Insights from LAPD Crime Data (2010-2023)”](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/image-57-218x150.png)

![[2024 Python with DS Project] 여름캠프 종료… 프로젝트 결과물 공개](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Python-with-DS-closing-ceremony-3-218x150.png)

![[ASK교육] 유명세보다는 ‘본질’, 대학의 진짜 실력을 따져라](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image-61-100x70.png)

![[학자금 칼럼] 평균 지원 비율 따져보자…내역서 분석 어필의 핵심](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image-56-100x70.png)

![[ASK 교육] 명문대 입시 전략의 핵심 카드는 ‘ED’](https://edubridgeplus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/image-17-100x70.png)